Geometric City's Editorials

by Jonas Berthod, Marie-Mam Sai Bellier, Nicolas Pirus

Jonas Berthod in Revue Diorama No.2, Geometric City, p.12.

The traces left by artists, designers, writers and activists make it possible to portray the mood of an era —its concerns and its hopes— more subtly than historical records. In the 1950s, a predominantly optimistic impulse prevailed. In his studio-laboratory, Vasarely was busy finding new horizons. He was looking for a form of social art involving the masses, [1] feeling that “future is emerging with the new geometric city, polychrome and solar. Plastic art will be kinetic, multidimensional and communal, abstract for sure, and close to the science” [2]. The second issue of Diorama borrows this optimistic quote from the artist-engineer as a starting point.

Vasarely, like many others, had almost absolute confidence in modernism and technological progress. The new city and the community masses to which he referred echo the social housing programmes that were then expanding at an international level. But the optimism for these housing projects, grands ensembles or New Towns barely lasted a generation.

Admittedly, the city is now omnipresent in our lives. It is visible in this issue of Diorama in architectonics, images or typefaces that sometimes recall the painter’s geometric compositions. However, the vivid imagination of the twentieth-century science fiction seems to no longer have currency. The current mood exudes a vague apprehension about an uncertain future where faith in technology has given way to a more cautious approach.

In the summer of 2019 alone, we saw —in no particular order— the Amazon and Indonesia set on fire; about 140 shootings taking place in the United States with general indifference; media personalities implying that they wished the death of Greta Thunberg, who was crossing the Atlantic by sailboat to protest against the climate emergency; unprecedented violence against mostly peaceful demonstrators in Hong Kong, Moscow or Warsaw; not to mention the attacks, massacres and missile exchanges that continue to punctuate the news cycle.

A quick look back over the shoulder, if only as far as a quarter, highlights the discrepancy with the artist’s optimistic vision. To quote Gibson, “the future has arrived —it’s just not evenly distributed yet” [3]. Does it reside in Tokyo, the West’s futuristic city par excellence, or is it better located in the soybean fields that have replaced the rainforests? What would Vasarely’s notes contain if he was a witness to our future? From Afrofuturism to algorithmic poetry, from synthetic paving stones to public sculpture, this issue offers a selection of possibilities. They often show restraint and, while not fatalistic, are reluctant in their projections. Would it be possible otherwise? The future is shaping up with caution, circumspection and questioning.

Marie-Mam Sai Bellier & Nicolas Pirus in Revue Diorama No.2, Geometric City, p.14.

It’s under the tarnished lights of the Geometric city’s leftovers that we re-read Victor Vasarely’s thoughts. These words which built it up yesterday, today strike a door between to worlds: confronting the authoritarian utopias of one era to the disordered desires of another. Now, the city rustles with calls of urgency in cries of revolt which resound in chorus. A thousand voices demand the advent of dream cities not for everone but by all, day and night. The future is not geometrical, it is not solar, it is not singular as in the words of Victor Vasarely. It is now plural, protean and conjugates at all times. This issue propose to explore this story in regard to what it generated.

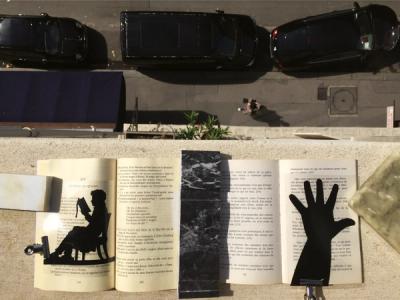

Confronting the projections of two times, this issue of Diorama whishes to address this past vision of the future to a genereation of authors speaking from the geometric world. A mistrust is expressed against the mechanisms of progress —the great gear of the capitalist machine— and the History, which is no longer the paved road of a glorious march. To this path are preferred shadows crossroads, where you choose to create futures. To make them no longer by lines, blocks and walls, but by our hands, our bodies and our words. The dreams of concrete and rocket fall in pieces under the words of Antoine Boj and Raoul Audouin. The polychromatic sensuality looks for a body in Floris Dutoit’s painting. An organic and not mechanical vision of the world is emerging, an organicity that is not opposed to technology, but open spaces for meetings and collaboration. Places where one can, like Aurece Vettier, learn poetry to machines and hear singing in chorus humans and I.A with Peter Collagen and Cyber Diva.

This coexistence between architecture, technique and living resonates with the invitation of Jean Alessandrini. We find today in his work an organic graphic, alive, anachronistic and rich of stories. The body-words and body-types that he draws are ready to lead a fantasy revolution, in a city populated by metatexts. At the heart of this polyphony, these organic and sensual worlds are opposed to the geometrical coldness of the Vasarelians new worlds.

The typography designed for this issue encapsulates the legacies of Pop art and Optical art. It pushes the search for geometric synthesis to labyrinthine and encrypted forms. Mazes to stroll in the video game accompanying this issue. This virtual diorama takes the contributions as a world of letters to explore.

If we want plurals and complexes future, the forms we create today must think and populate them, as “Giraffe” by Motoki Nakatani & Shinnosuke Miyamoto. This ghostly being, who seems to have camouflaged his physiognomy, finds in the forms of the geometrical city the artifices of its obscuration. A darkness that allows us to rebuilt our world, and to live our singularities in the shadow of abstract cities and an history in failure.

- Victor Vasarely, Notes Brutes (Paris : Denoël / Gonthier, 1973)

- Ibid.

- William Gibson cité dans Scott Rosenberg, « Virtual Reality Check Digital Daydreams, Cyberspace Nightmares », San Francisco Examiner, 19 avril 1992